The Secret Fragrance Traditions of the African Kingdom of Kerma

When most Americans think about ancient perfumes, Egypt or Mesopotamia often come to mind. Yet, one of the earliest centers of fragrance traditions in Africa lies further south—in the Kingdom of Kerma.

This Nubian civilization, which thrived between 2500 and 1500 BCE in present-day Sudan, developed unique fragrance practices that blended local resources with international trade. Their story adds a fascinating chapter to the broader history of perfumes and helps us see how African perfumes shaped global culture long before modern fragrance industries.

The Kingdom of Kerma: A Hidden Gem in African History:

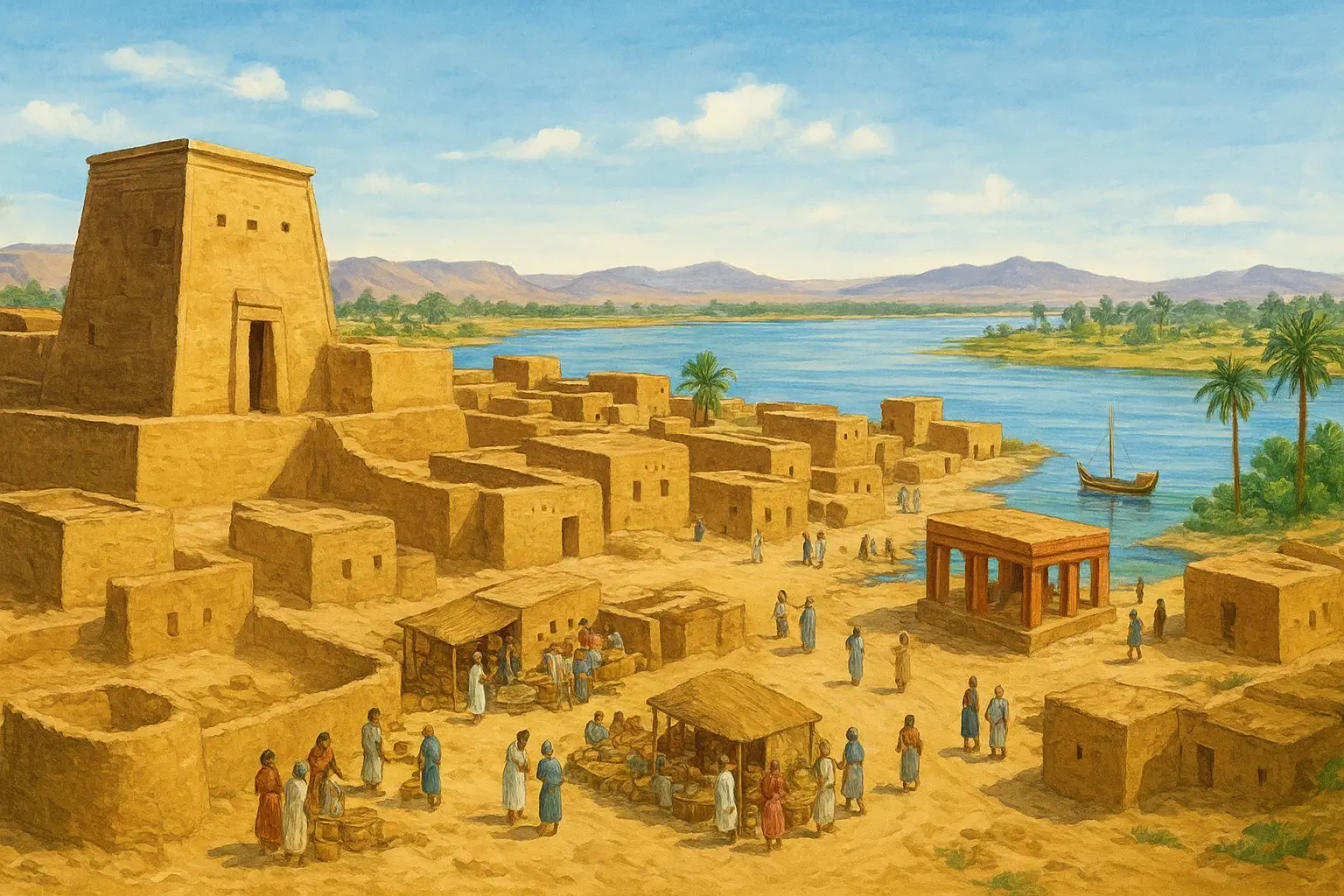

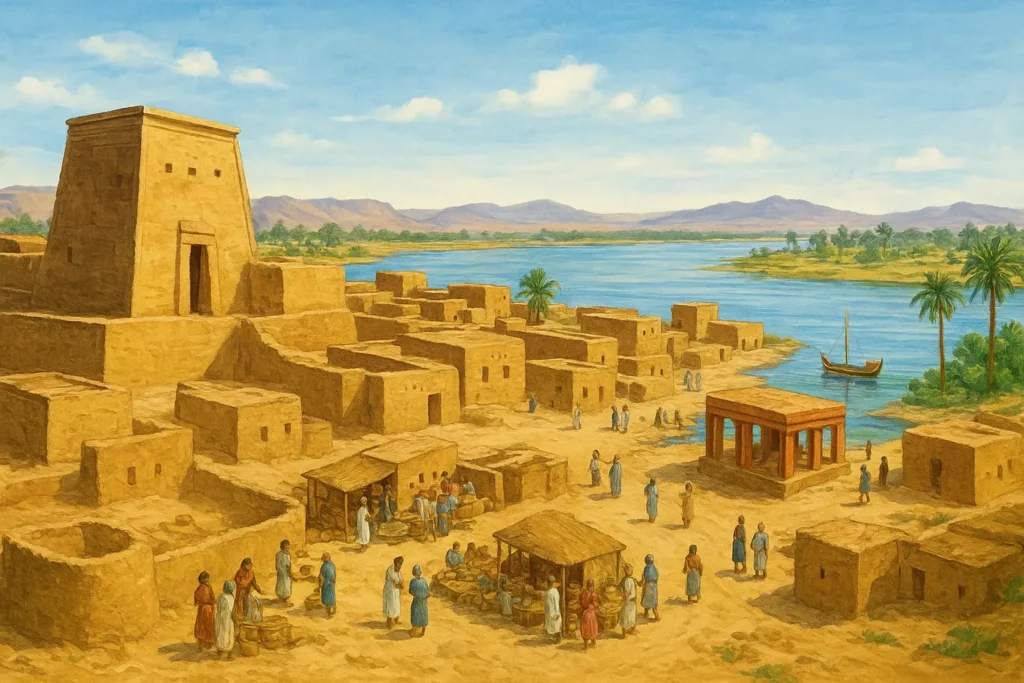

Kerma was one of the most powerful ancient African kingdoms, rivaling Egypt in wealth and influence. Archaeologists describe it as the first true kingdom in sub-Saharan Africa, with monumental architecture, strong leadership, and thriving trade.

While often overshadowed by its northern neighbor Egypt, Kerma had its own distinct cultural identity. Central to that culture were rituals of scent and incense, where perfumes were not just luxuries but spiritual and political tools.

For Americans familiar with ancient Egypt’s fascination with perfumes, Kerma offers a new lens: a society that embraced fragrance traditions not as borrowed ideas but as core elements of its civilization. This positions Kerma as an important, though often overlooked, contributor to the history of perfumes.

Natural Ingredients: Fragrance from the Land of Nubia:

The Nubian landscape provided Kerma with a treasure trove of aromatic resources. Resins like myrrh and frankincense, desert herbs, and rare woods were among the prized ingredients. Archaeological excavations reveal that incense burners and containers for aromatic oils were common in both temples and elite burials. These discoveries suggest that ancient fragrances were deeply embedded in daily and ceremonial life.

Unlike imported perfumes that flowed from Egypt and the Levant, Kerma cultivated its own blend of local plants and resins. This made their African perfumes unique in scent and symbolism. For example, desert herbs were believed to ward off evil, while resins were seen as offerings pleasing to the gods. In American terms, it was as if perfume functioned like both fine cologne and sacred incense, holding social, spiritual, and protective roles.

Fragrance in Rituals and Religion:

For the people of Kerma, fragrance was more than sensory pleasure—it was sacred. Temples were filled with the smoke of incense, a visible symbol of prayers rising to the heavens. Priests purified themselves and their spaces with aromatic oils before engaging in rituals. Kings and queens were often buried with vessels of fragrant oils and incense, suggesting that the afterlife would be as perfumed as the earthly world.

In this way, Kerma’s fragrance traditions mirrored but also differed from Egyptian practices. While Egypt often emphasized perfume as a marker of luxury and divine favor, Kerma placed equal emphasis on its protective and communal qualities. Every ritual—from healing ceremonies to state functions—was infused with the transformative power of scent.

Imagine an ancient Nubian temple: the air thick with frankincense smoke, drums echoing, priests chanting, and perfumes rising skyward. This immersive use of scent helped create an atmosphere that blended human devotion with divine presence. For modern Americans used to perfume as a personal accessory, Kerma’s approach reminds us that fragrance can shape collective experience.

Trade and Global Influence:

One of the most remarkable aspects of Kerma’s perfume culture was its role in the early incense trade. Strategically located along the Nile, Kerma became a hub connecting sub-Saharan Africa with Egypt and the Mediterranean world. Caravans loaded with African perfumes, incense, and resins traveled north, where these exotic goods became coveted luxuries in Egyptian temples and royal courts.

This trade was not one-directional. In exchange, Kerma received luxury items such as jewelry, fine pottery, and perhaps even finished Egyptian perfumes. These exchanges positioned Kerma not only as a consumer of global fragrance traditions but also as a key exporter that shaped the history of perfumes far beyond Africa.

In fact, some scholars argue that the global fascination with resin-based perfumes—from Greece and Rome to Arabia—has roots in Nubian exports. When Americans enjoy woody, resinous perfumes today, they are, in a sense, inhaling echoes of Kerma’s ancient trade.

Fragrance and Social Identity:

Perfume in Kerma was also a marker of identity and hierarchy. The elite classes had privileged access to imported resins and fine oils, while common people relied on local herbs and simpler blends. This distinction mirrored social divisions, where fragrance reinforced power and prestige.

At the same time, perfumes were not restricted to the wealthy alone. Ceremonial events often included community-wide incense burning, ensuring that even ordinary citizens experienced the sacred role of fragrance. In this sense, Kerma’s fragrance traditions balanced exclusivity with communal participation.

For Americans today, where perfumes are often marketed as symbols of individuality and status, Kerma offers a reminder of fragrance as a communal and spiritual resource.

Archaeological Evidence: Traces of Scent in Stone:

Archaeologists working in Kerma have uncovered incense burners, jars, and burial goods that strongly point to the significance of perfume. Residues of aromatic substances have been detected in some vessels, confirming that ancient fragrances were indeed part of everyday and ritual life. Large burial mounds, known as tumuli, often contained both luxury goods and incense containers, showing how scent accompanied the dead into eternity.

The evidence paints a vivid picture: fragrance was not just temporary, evaporating into thin air, but an enduring cultural marker. The physical remains—stone burners, pottery jars—anchor Kerma’s perfumes in history and allow us to reconstruct their role with surprising clarity.

The Legacy of Kerma’s Fragrance Traditions:

Although the Kingdom of Kerma eventually declined under Egyptian expansion, its fragrance traditions lived on. Nubian scents such as myrrh and frankincense became staples in Egyptian religion, Mediterranean trade, and later even Roman rituals. The influence of Kerma extended well beyond its borders, contributing to the global history of perfumes.

Today, when Americans pick up a perfume that carries notes of resin, spice, or wood, they may unknowingly be smelling ingredients once prized in Kerma. The kingdom’s legacy survives in every spritz of fragrance that draws from the same desert plants and sacred resins.

Conclusion:

The secret fragrance traditions of the African Kingdom of Kerma remind us that perfume is more than a luxury—it is a cultural language. Kerma’s use of fragrance connected the living to the divine, marked social identity, and fueled international trade. For Americans curious about the global roots of perfume, Kerma offers a story that is exotic yet profoundly relatable.

The next time you enjoy your favorite fragrance, pause to imagine a Nubian king or priest, standing in a temple filled with incense, connecting their world to the divine through scent. It’s a reminder that perfume has always been more than aroma—it has been a bridge between people, beliefs, and civilizations.

Call to Action: Share your thoughts—what role does fragrance play in your own life? Could it be more than just a personal accessory, perhaps even a connection to something larger, as it was for the people of Kerma?

Discover more from Perfume Cultures

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.